If you’re teaching the new IBDP Psychology syllabus (first exams in 2027, first lessons next week!!!), you already know how much planning, organising, and resourcing it takes to cover everything—concepts, content, contexts, the internal assessment, and exam preparation. That’s why this complete PowerPoint bundle has been created: to give you a ready-made, fully editable set of presentations that match the new Subject Guide and Tom Coster’s IB Diploma Psychology – The Textbook perfectly.

Visit this page to read more.

This isn’t just a slide deck or two—it’s the WHOLE COURSE in one place. Sixteen separate presentations walk you and your students through every key concept (Bias, Causality, Change, Measurement, Perspective, Responsibility), every content area (the biological, cognitive, and sociocultural approaches, plus research methodology), and every context (Health & well-being, Human development, Human relationships, Cognition & learning). You’ll also find dedicated presentations for the Internal Assessment and for exam strategies, so you can guide students from their first class right through to their final paper.

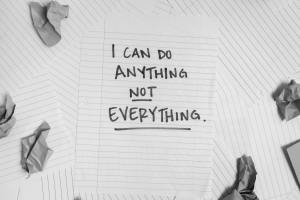

Because they’re fully editable, you can add, remove, and adapt slides to fit your own teaching style or the particular needs of your students. Want more emphasis on a tricky theory? Less on a topic your class already knows? You’re in control. The presentations are ready to use straight away—but they can be as flexible as you need them to be.

To get a feel for the style and structure, there’s a free sample presentation you can download and try in your next lesson. And the full bundle? Just $50 for hundreds of hours of preparation already done for you—available as an instant download, no delivery time, no waiting.

In short, this is about saving your time, reducing your workload, and giving your students consistent, high-quality resources from day one.